Biologists at UC San Diego Identify Key Protein in Cell's "Self-Eating" Function

MARCH 11, 2008

Media Contact: Paul K. Mueller 858-534-8564

Comment: Suresh Subramani 858-534-2327

Jean-Claude Farré 858-534-3092

Molecular biologists at the University of California, San Diego have found one piece of the complex puzzle of autophagy, the process of "self-eating" performed by all eukaryotic cells - cells with a nucleus - to keep themselves healthy.

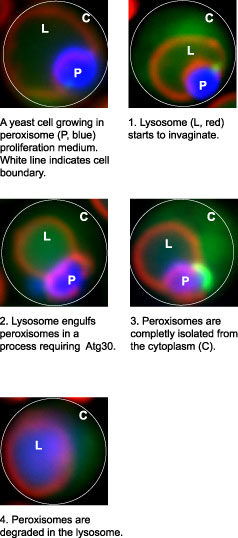

Illustration of a yeast cell invaginating a peroxisome, which is then engulfed in a lysosome in a process requiring the protein Atg30. The peroxisome is then degraded in the lysosome.

Their finding, published in the March 11 issue of the journal Developmental Cell, is important because it allows scientists to control this one aspect of cellular autophagy, and may lead to the ability to control other selective "self-eating" processes. This, in turn, could help illuminate autophagy's role in aging, immunity, neurodegeneration and cancer.

All eukaryotic cells dispose of bacteria, viruses, damaged organelles and other non-essential components through this self-eating process. A part of the cell called the lysosome engulfs and degrades subcellular detritus. The ability of cells to recycle and reuse the cellular raw materials, as well as to "re-model" themselves in response to changing conditions, allows them to adapt and survive.

Autophagy was first described about 40 years ago, but has recently become a topic of great interest in cell biology because it is linked to cell growth, development aging and homeostasis -- helping cells to maintain a balance among synthesis, degradation and recycling.

The UC San Diego researchers report in their paper that they identified a novel protein called Atg30 (one of 31 required for autophagy-related processes) from the yeast Pichia pastoris, that controls the degradation of a sub-compartment of cells, the peroxisomes.

Peroxisomes generate and dispose of harmful peroxides that are by-products of oxidative chemical reactions.

Different organelles within the cell are degraded by lysosomes when the organelles are damaged or not necessary, said Jean-Claude Farré, the biologist who identified Atg30. The team is investigating peroxisomes, and working to understand how and why they are selected by the lysosome for degradation.

What the biologists found, he said, is that "this new protein can mediate peroxisome selection during pexophagy - that is, it is necessary for pexophagy, but not for other autophagy-related processes."

Suresh Subramani, a professor of biology who headed the team, said they have established that Atg30 is a "key player" in the selection of peroxisomes for delivery to "the autophagy machinery" for re-cycling.

"For the first time, we can use a protein to control the process," Subramani said. "It's an important step in understanding the workings of cells."

Subramani and Farré were assisted by Ravi Manjithaya and Richard D. Mathewson, all of the Division of Biological Sciences at UC San Diego.

The study was funded by grants from the National Institutes of Health.