Time to Rock and Roach: Bringing Experiments from the Lab to the Home

With pandemic at-home restrictions, Biological Sciences faculty develop inclusive solutions for students to engage in cool hands-on science

May 10, 2021

By Kritin Karkare

Ashley Juavinett

When you're in a lab class, what you learn and do in the lab stays in the lab. But what happens when your own home becomes the lab? With the global COVID-19 pandemic forcing many biology students out and away from the traditional lab setting, Division of Biological Sciences professors at UC San Diego had to rethink what it meant to do hands-on activities. Their solution? To bring the science home to the students using lab kits they developed (cockroaches sometimes included).

Yes. You read that right - here's one professor who's sending cockroaches to your home for science.

-----

In normal times, when a pandemic has not shuttered campus lab classroom doors, students in the Neurobiology Lab class get to try out lots of different techniques that researchers use to learn about the nervous system. There are organisms aplenty to investigate: earthworms that get their nerve cords stimulated, leeches whose neurons get poked and even humans, who record their own brain activity.

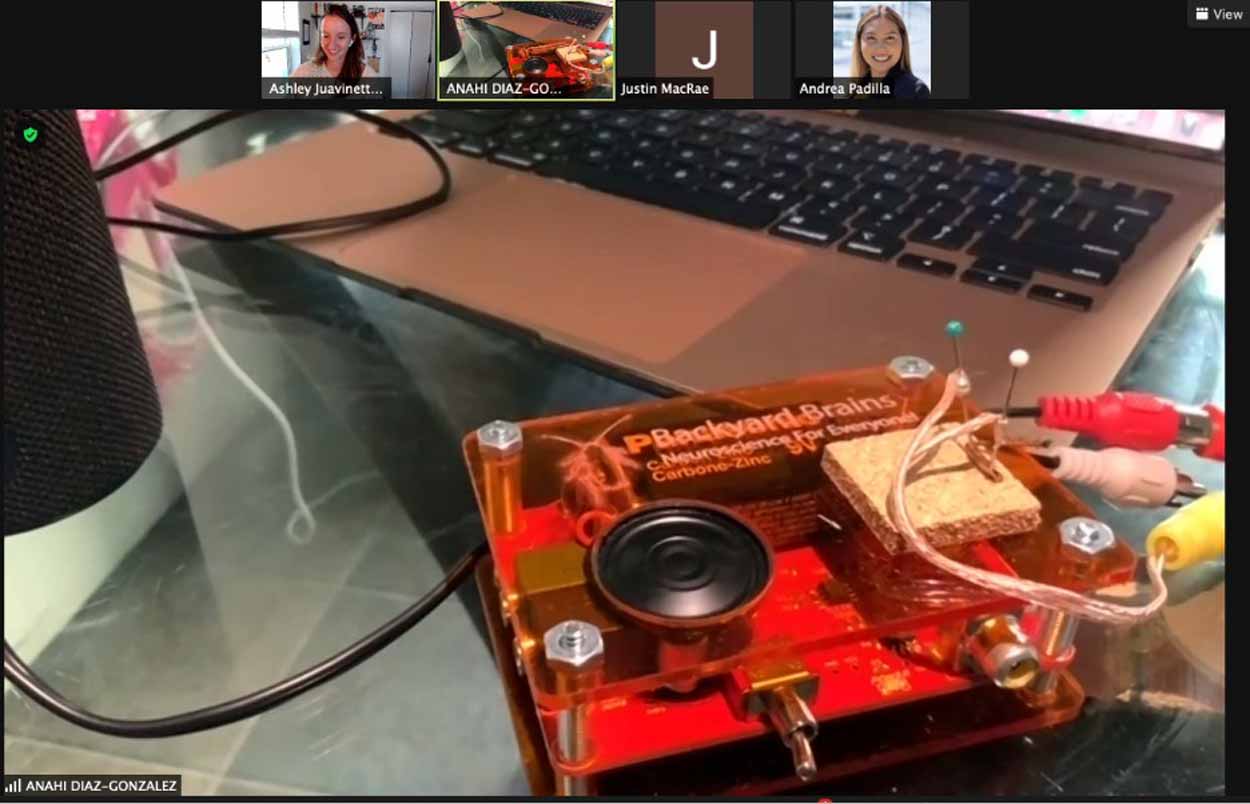

Experiments like these, however, are just a teensy bit difficult to carry out when no one can get inside the classroom. That's when Ashley Juavinett, the teaching professor in charge of the class, got thinking.

As a graduate student, Juavinett was heavily involved with the UC San Diego Neuroscience Outreach Program, which travels to local schools and events like the San Diego Festival for Science and Engineering to teach children how the brain works. One of the most common tools they used was a small device called a SpikerBox, developed by a company called Backyard Brains. This SpikerBox, which amplifies and records neural signals in real time, lets budding neuroscientists in training explore what makes neurons tick in different creatures, including cockroaches.

A cockroach from the Neurobiology Lab kit

For Juavinett, implementing this kit with the cockroaches seemed like the best idea.

"It's a simple experiment, but if we're thinking of sending kits home to students where they have to do the kits themselves, it works out really well that it's straightforward," Juavinett says.

Shipping these bugs out was not an easy task, however, as Juavinett found out, there were many challenges involved, ranging from how safe it was to mail live insects to whether such critters would even survive the journey.

Thanks to the hard work of Melissa Micou, Dennis Hickey and the UC San Diego Biology Instructional Lab team, they were able to get the clearance to mail the insects out. Staff Research Associate Brandon Chechile helped pack the cockroaches with care for a successful journey to the students' mailboxes.

Thus, with new friends on the way to the students' home,' the class was then ready to start the experiment in their improvised laboratories.

Experiment 1 2 3

The first task to investigate the nervous system of the newfound buddy, Juavinett says, is to anesthetize the cockroach so you can pull its leg off. Don't sweat too much about the fact that you took off the leg: it'll grow it back in a few months. Each cockroach has thorns on the side of its legs with sensory neurons nearby to alert the central nervous system of any stimulation. By touching the thorn, you can elicit firing in the neurons and do experiments to test which thorns elicit the most activity.

Neurobiology Lab kit Setup

But then day 2 is when the science gets groovy-musically groovy.

Instead of recording the action potentials, you can hook up the cockroach leg to an audio output and then send the song to the cockroach leg-this stimulates the legs, which in turn start moving in rhythm to the song. The goal here though isn't to admire the cockroach's dancing abilities-you can actually learn about what might be the best method to get the most activity out of the cockroaches' legs.

Students tried all different kinds of songs and artists like Gold Stupid Love by Excision and Illenium and New Rules by Dua Lipa; they even experimented with classical music. The conclusion? Bass drives cockroach legs the best (see video here).

Left to right: Stephanie Mel, Stanley Lo, Keefe Reuther

If cockroach legs bopping to the beat made you queasy, perhaps professors Stanley Lo, Stephanie Mel and Keefe Reuther, head instructors for the Intro to Biology Lab course (BILD 4), can offer you a more grounded activity.

Digging Deeper

In the Intro to Biology lab, students go out on a field trip to collect soil samples from the nearby Scripps Coastal Reserve and then bring them back to categorize their microbial diversity. From there, students perform DNA extraction on the soil and then get that sequenced to find out which ones are native and non-native. According to Lo, it's an introduction to research for all the first years that lets them get their feet dirty and engage in real research from the beginning of their university careers.

But with most students quarantined at home, and even some as far away as India or China, field trips are but a pipe dream. Moreover, unlike the Neurobiology Lab course, which enrolled around 45 students in fall, Lo, Mel and Reuther's course had over 800 enrolled!

That didn't stop the professors from experimenting. Like Juavinett, they also started to brainstorm in-person activities that could be done by students easily and could be scaled.

Soil corer

They found their answer: all students had to do was use a small tool called a soil corer to scoop out two batches of soil from any plant around them, plop them into the tubes provided, and send them back to UC San Diego for sequencing so they could characterize the soil bacterial microbiome. Then the three of them dug deeper-this could be an opportunity to get soil samples from around the United States and even the world! While the data would not be as clean as the data from the typical collection site, the Scripps Coastal Reserve, the data could help both the students and professors learn about the rich microbial global diversity of soil.

Normally, students don't physically collect samples from the Reserve. "But the fact is now, the soil has a personal connection to them. And I think that's actually important-there's a much more sense of ownership if the students have their own personal sample," Mel says. And thanks to the help of Lab Assistants Kenneth Edwards, Jamie Sanchez and Bobby Waddell from the Instructional Lab team in assembling all of these kits, the BILD 4 team made that goal of personal samples for the students a reality.

Cutting Edge Technology Right at Home

Perhaps you are not in the mood to let any of the outside world come through your front door. Lisa McDonnell, head instructor for the Recombinant DNA Techniques lab class (BIMM 101), might have the solution for you. McDonnell, together with Claire Meaders, another instructor for BIMM 101, and Staff Research Associate Andrew Moore, who was critical to helping test, troubleshoot and refine the experiment protocol for BIMM 101, developed a kit that lets students use CRISPR gene editing technology without having to leave their house.

Left: Lisa McDonnell, Right: Claire Meaders

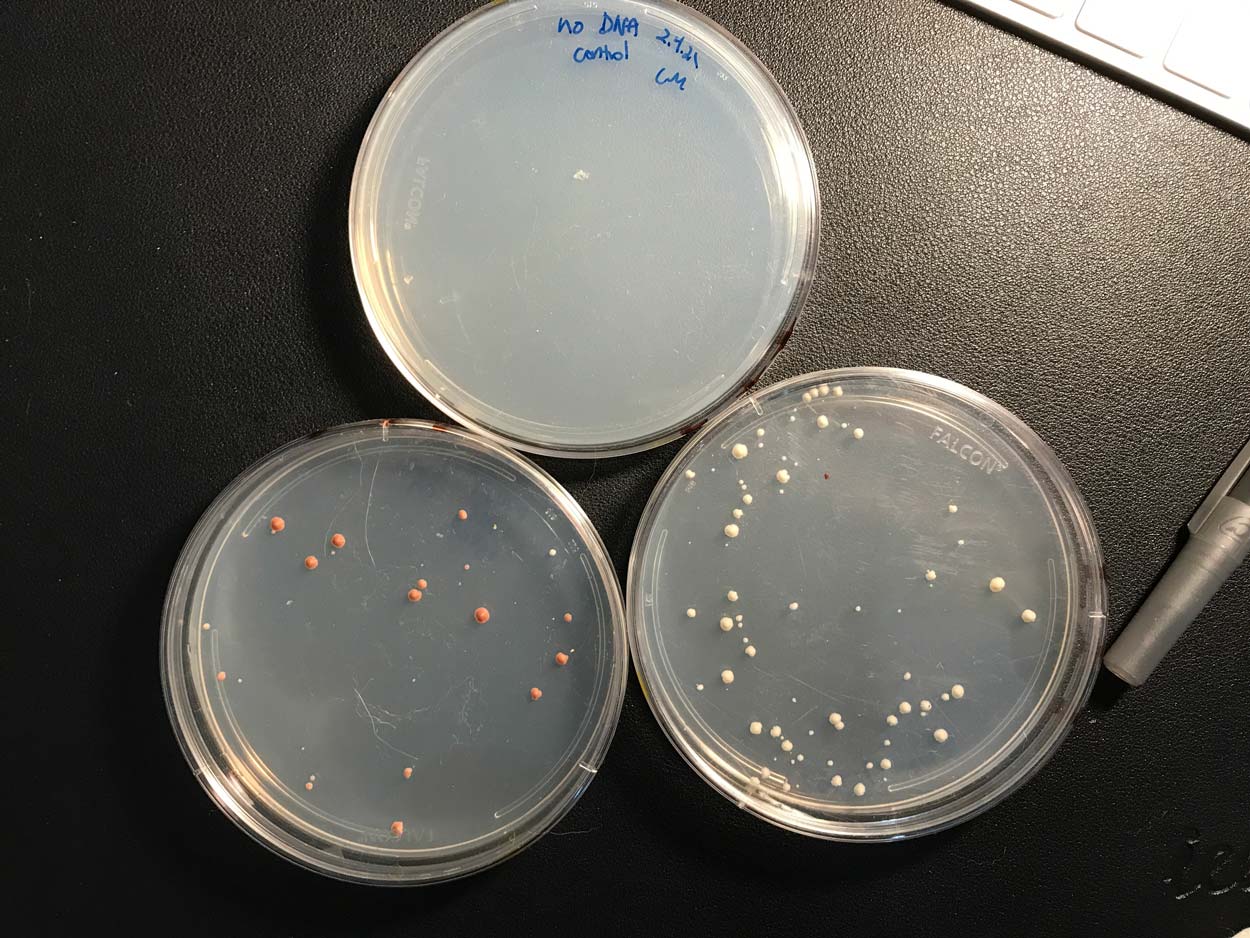

Her kit contained all the materials needed to grow and transform yeast so the yeast could express the endonuclease Cas9 and a guide RNA. Combined, the Cas9+gRNA can target and cut the ADE2 gene. If loss of function mutations were introduced into the gene after Cas9 cutting, the yeast colonies turn red. After transformations, students were able to send yeast samples back to the Instructional Labs for sequencing to determine the precise genetic changes that occurred. Using the results collected, students were able to determine the frequency of both random mutations introduced after Cas9 cutting, as well as the frequency of targeted mutations introduced by encouraging a process known as homology directed repair.

Katie Petrie

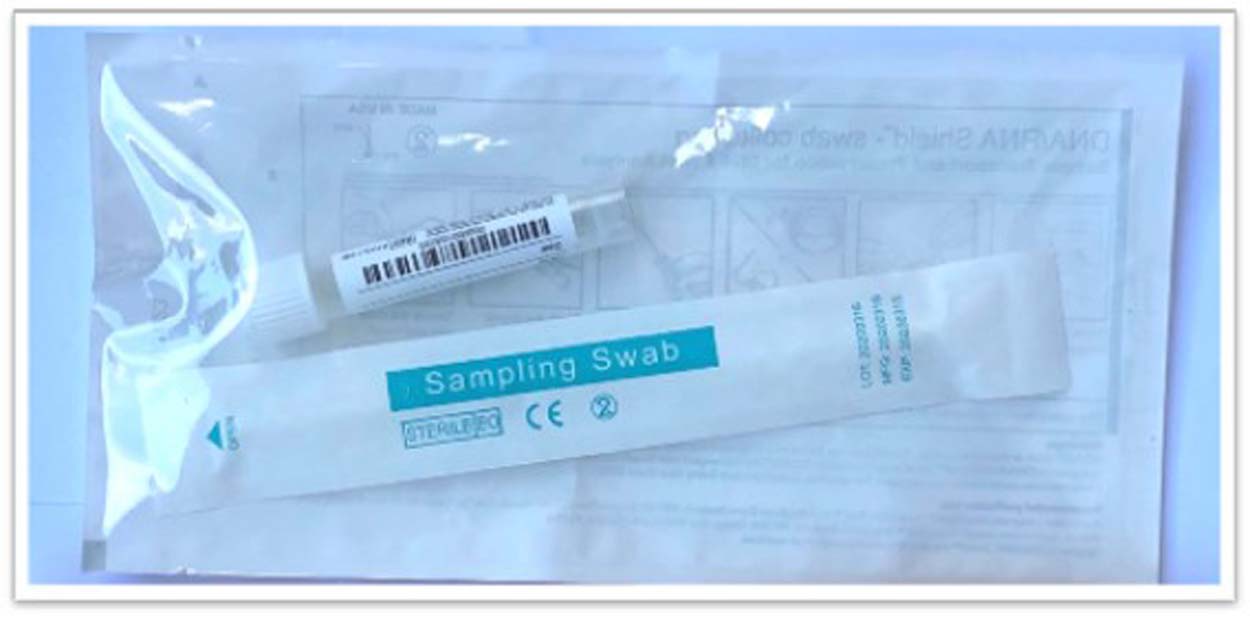

Curious about the critters that you can't see? Katie Petrie, head instructor for the Microbiology Lab class (BIMM 121), wanted to find out what kind of microbes are found in the built environment. Since students were stuck at home, she figured students could take a closer look at the place where they were spending so much time. Students came up with different surfaces to compare in their homes (example: floors of homes with dogs vs floors of homes without), then sampled the surfaces using a swab very similar to what you might see in a self-administered COVID-19 test. These swabs, containing microbes picked up from the surface, were placed in a tube of pathogen-inactivating preservative and then shipped back to the Instructional Labs. Then, Staff Research Associate Ana Gomez, who also assembled the BIMM 121 kits, helped process their samples for 16S metagenomic sequencing analysis using the Instructional Lab's Illumina MiSeq DNA sequencing machine. Students then practiced their newly learned bioinformatics cloud computing skills to determine the composition of microbes in each environment and see if there were differences.

Charting New Lab Territory

Swab and preservative from Microbiology Lab kit

Indeed, the change in curriculum and focus due to remote learning has brought everyone into unfamiliar lands.

"We're learning a lot of new things. This course has been running for the past six years and we've settled into a pattern and hadn't thought about these opportunities." says Lo. He also described that because of the remote learning, the Intro to Biology lab course could focus on aspects of research that get much less priority in a lab class, like scientific writing and discussion, skills that are essential to talking about science.

About 80% of students who responded to an end-of-course survey agreed or strongly agreed that the home-kit experiments helped them apply the concepts learned in the course and made molecular biology feel more real. Another student said "it was so fun to be able to actually do the experiment. Opening the box and seeing all of the tools and samples brought so much joy to my day and then when I actually had colonies grow red I was super excited."

Plus, the kits are not just a way to add hands-on learning–they have made remote learning more inclusive. In virtual learning, not all students have equal access to technology; some may not have stable internet connections and others may not have a quiet space to work in. "The nice thing about the lab kits," Reuther says, "is that students don't need any other additional tools." In turn, it lowers the barrier to engaging in the lab activity.

Yeast colonies

These lab kits also help break down other kinds of barriers. When Juavinett asked how many of her students talked about the cockroaches to someone close to them like a roommate or family member, more than 70% said yes. She also asked if they had posted on social media–more than half also said they did.

"From a science communication standpoint, I find that really cool," Juavinett says. "Normally education literally happens within campus walls-students just go into the lab, use the equipment, and then they leave. But when you send science home to students, you bring it into their world and the people they spend time with. That's really interesting. You have to talk to your mom about why UC San Diego is sending cockroaches home-I'd love to be a fly on the wall for that conversation."

And if there was any room for doubt that the cockroaches might mount a campaign to conquer the house, Juavinett says that's unlikely. They can't easily propagate on their own, nor can they fly. That being said, she offered another idea besides throwing them out.

"They're pretty chill - you can even keep them as pets," jokes Juavinett. "If you give them food now and then, they're pretty easy to take care of."