Study of Tropical Forests Worldwide Reveals that Nature Encourages Diversity

January 26, 2006

By: Kim McDonald

An analysis of seven tropical forests around the world has found that nature encourages diversity by selecting for less common trees as the trees mature.

The landmark study, which was conducted by 33 ecologists from 12 countries and published in the January 27 issue of the journal Science, conclusively demonstrates that diversity matters and has ecological importance to tropical forests.

"Ecologists have debated for decades over whether there is something of ecological value to species diversity," says Christopher Wills, a professor of biology at the University of California, San Diego, who headed the study. "We found that in forests throughout the New and Old World tropics, older trees are more diverse than younger ones. In other words, diversity is actually selected for as each of the forests matures. This means diversity does indeed matter and is an essential property of these complex ecosystems."

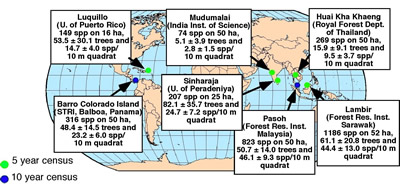

The study was conducted on seven undisturbed forest plots, or "tropical forest observatories," maintained and studied by research institutions in Borneo, India, Malaysia, Panama, Puerto Rico and Thailand, under the coordination of the Center for Tropical Forest Science of the Smithsonian Tropical Research Institute, based in Panama.

"The great scientific value of these tropical forest observatories is that each of them has undergone a complete census more than once, so that the researchers know what has happened to hundreds of thousands of trees from one census to the next," says Stuart Davies, the recently appointed director of the Center for Tropical Forest Science. "These tropical forest observatories, along with others in our network, represent some of the most important, detailed and long-running ecological studies in the world today."

In addition to the Smithsonian Tropical Research Institute, the institutions that manage the tropical forest observatories included in this study are the Indian Institute of Science, Royal Forest Department of Thailand, University of Peradeniya of Sri Lanka, University of Puerto Rico, and the Forest Research Institutes in Peninsular Malaysia and Sarawak.

The forest plots, two from the Americas and five from Asia, are themselves diverse. They range from dense and species-rich wet rainforest to drier and more open forest that is often swept by fires. Even so, all the forests show the same pattern of increasing local diversity as trees age.

"Each forest in our study is a highly dynamic community," says Kyle Harms, an assistant professor of biological sciences at Louisiana State University and a principal collaborator on the project. "We found that the diversity of each local area increased regardless of the species that were present. This is because trees that were locally common tended to die more often than those that were locally rare, giving a survival advantage to rare species." The effect was even seen within species, he adds. "If a species was common in one part of a plot and rare in another, its death rate was higher where it was common."

The effects found by the researchers are strong enough to increase local tree species diversity as trees age in all seven of the forests. But precisely what is responsible for the increases in diversity?

The authors cite three possibilities, all of which, they say, are likely to play a role: First, rare species may be at an advantage because the animals, fungi, bacteria and viruses that prey on them are less likely to cause damage when their hosts are rare. Second, the rare species may be at an advantage in competition for certain physical resources, because individuals of the same species tend to share more similar resource requirements than individuals of different species. And third, rare species would be at an advantage when tree species have direct, positive influences on one another, because trees of rare species are on average surrounded by a high proportion of trees that are different from themselves.

The scientists point out that none of these processes can operate in "monoculture" forests, where the individual trees are all of one particular species. Such forests are highly susceptible to diseases, and individuals are in direct competition with individuals like themselves.

The three diversity-enhancing processes are also likely to be absent from badly damaged forests. When forests are clear-cut, the soil is rapidly eroded, depleted of nutrients and the "invisible world" of insects, bacteria and fungi that help to sustain diversity largely disappears.

But the authors point out that their study suggests that tropical forests that have been damaged slightly, by carefully managed selective logging for example, should soon regain their former levels of diversity, provided the damage has not been severe or long-continued.

"If you damage a forest a little bit, the forest can recover," says Wills. "Even damaged ecosystems can be restored to their former diversity through natural processes if they are allowed to do so."

Wills says the new study points the way towards further detailed investigations of the processes by which forest diversity is maintained and raises new questions and lines of research for ecologists, and forest managers, to pursue.

"Are the same processes operating in temperate forests?" he asks. "How much damage can a forest sustain before its diversity begins to decline? Are other complex ecosystems, like coral reefs, also selected for increased diversity? This paper provides insights into a dynamic and evolving natural world and shows that diversity is not just an esthetic ideal, but is also an important property of natural ecosystems."

In addition to UCSD, LSU and the institutions that managed the tropical forest observatories, other institutions with researchers who contributed to the collection and analysis of data for the study include Harvard University, University of Alberta, University of Minnesota, University of Georgia, Nanyang Technological University in Singapore, Thai National Park Wildlife and Plant Conservation Department, Field Museum, Florida State University, Osaka City University in Japan, University of Illinois, Thammasat University in Thailand and Tunghai University in Taiwan. The study was financed by grants from the National Science Foundation and the Center for Tropical Forest Science of the Smithsonian Tropical Research Institute.