Fly Model Offers New Approach to Unraveling ‘Difficult’ Pathogen

Transgenic fruit flies help scientists trace the cascade of symptoms caused by toxic infection

February 5, 2020

By Mario Aguilera

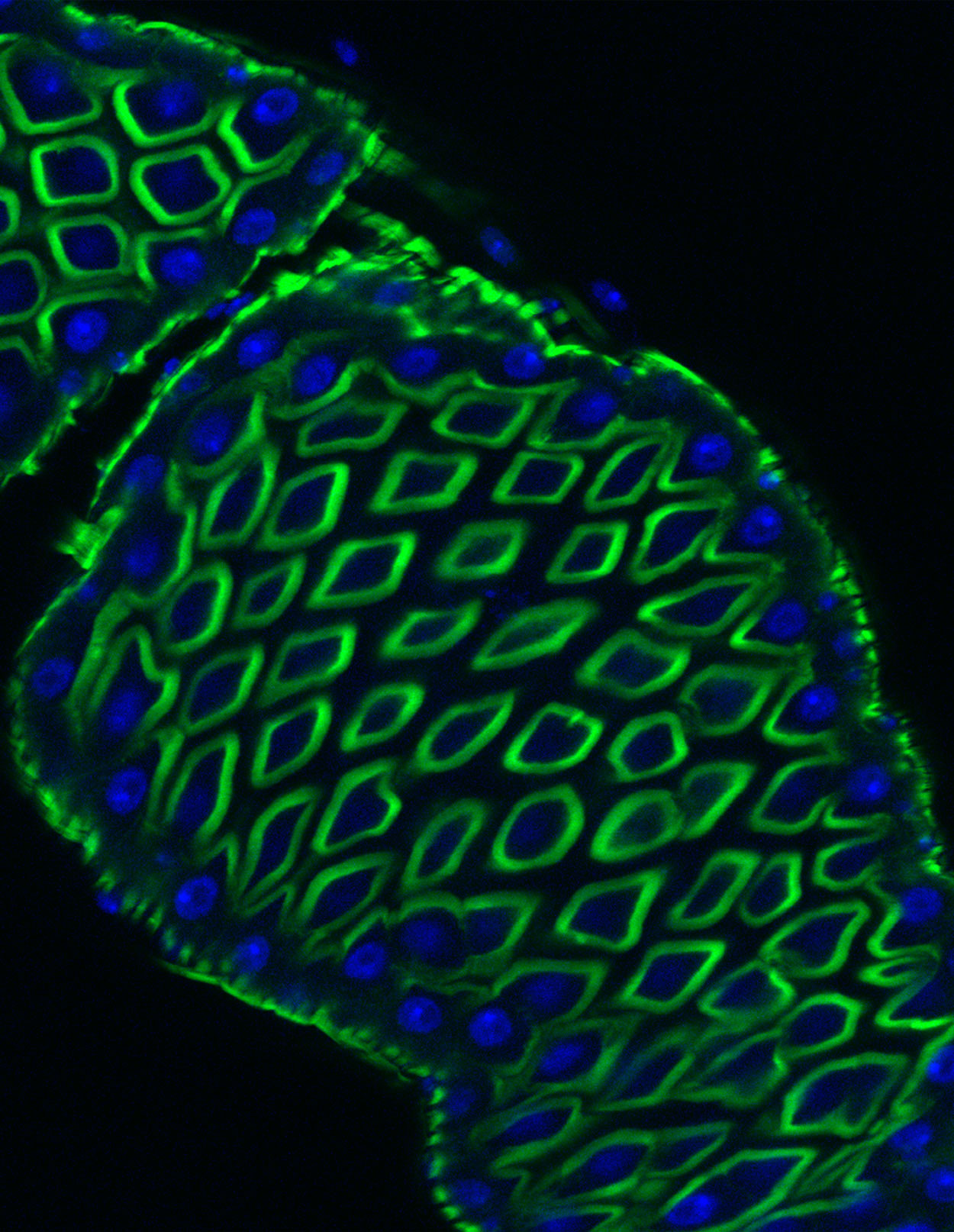

A normal fruit fly gut revealing the regular structure of actin staining microvilli (green) and cell nuclei (blue). This organization in the fruit fly is very similar to that of the human intestine. A study published in iScience makes use of these close parallels in structure and function to identify new activities of a toxin produced by the problematic hospital pathogen C. difficile.

Bier Lab, UC San Diego

The Clostridium difficile pathogen takes its name from the French word for “difficult.” A bacterium that is known to cause symptoms ranging from diarrhea to life-threatening colon damage, C. difficile is part of a growing epidemic of concern for the elderly and patients on antibiotics.

Outbreaks of C. difficile-infected cases have progressively increased in Western countries, with 29,000 reported deaths per year in the United States alone.

Now, biologists at the University of California San Diego are drawing parallels from newly developed models of the common fruit fly to help lay the foundation for novel therapies to fight the pathogen’s spread. Their report is published in the journal iScience.

“C. difficile infections pose a serious risk to hospitalized patients” said Ethan Bier, a distinguished professor in the Division of Biological Sciences and science director of the UC San Diego unit of the Tata Institute for Genetics and Society (TIGS). “This research opens a new avenue for understanding how this pathogen gains an advantage over other beneficial bacteria in the human microbiome through its production of toxic factors. Such knowledge could aid in devising strategies to contain this pathogen and reduce the great suffering it causes.”

As with most bacterial pathogens, C. difficile secretes toxins that enter host cells, disrupt key signaling pathways and weaken the host’s normal defense mechanisms. The most potent strains of C. difficile unleash a two-component toxin that triggers a string of complex cellular responses, culminating in the formation of long membrane protrusions that allow the bacteria to attach more effectively to host cells.

UC San Diego scientists in Bier’s lab created strains of fruit flies that are capable of expressing the active component of this toxin, known as “CDTa.” The strains allowed them to study the elaborate mechanisms underlying CDTa toxicity in a live model system focused on the gut, which is key since the digestive system of these small flies is surprisingly similar to that of humans.

“The fly gut provides a rapid and surprisingly accurate model for the human intestine, which is the site of infection by C. difficile,” said Bier. “The vast array of sophisticated genetic tools in flies can identify new mechanisms for how toxic factors produced by bacteria disrupt cellular processes and molecular pathways. Such discoveries, once validated in a mammalian system or human cells, can lead to novel treatments for preventing or reducing the severity of C. difficile infections.”

The fruit fly model gave the researchers a clear path to examine genetic interactions disrupted at the hands of CDTa. They ultimately found that the toxin induces a collapse of networks that are essential for nutrient absorption. As a result, the model flies’ body weight, fecal output and overall lifespan were severely reduced, mimicking symptoms in human C. difficile-infected patients.

In addition to Bier, study coauthors include first-author Ruth Schwartz, Annabel Guichard, Nathalie Franc and Sitara Roy.

The National Institutes of Health (R01 AI110713) funded the research.