Study Finds Future 'Battlegrounds' for Conservation Very Different to Those in Past

February 27, 2008

By: Kim McDonald

Spectral Tarsier in Sulawesi, one of the areas under threat.

Cagan Sekercioglu

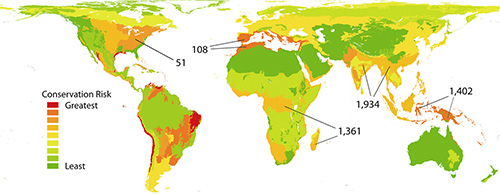

Fig 1: In the face of impending global change, some regions are more in need of protected lands than others. The map shows regions color-ranked by how much area is projected to change by 2100 in relation to how much area is currently protected ("Conservation Risk"). Many of the tropical, but not temperate regions with greatest risk (red) are also of highest conservation value as indicated by their higher number of globally unique amphibians, birds, mammals and reptiles. High change-protection ratio and much unique biodiversity combine to high conservation need (see Fig 2).

Biologists at the University of California, San Diego have developed a series of global maps that show where projected habitat loss and climate change are expected to drive the need for future reserves to prevent biodiversity loss.

Their study, published online today in the journal Proceedings of the Royal Society B, provides a guide for conservationists of the areas of our planet where conservation investments would have the most impact in the future to limit extinctions and damage to ecosystems due to rapid human-driven climate and land-use change.

The researchers found that many of the regions that face the greatest habitat change in relation to the amount of land currently protected -such as Indonesia and Madagascar-are in globally threatened and endemic species-rich, developing tropical nations that have the fewest resources for conservation. Conversely, many of the temperate regions of the planet with an already expansive network of reserves are in countries-such as Austria, Germany and Switzerland-with the greatest financial resources for conservation efforts, but comparatively less biodiversity under threat.

"There's a huge discrepancy between where the world's conservation resources are concentrated and where the greatest threats to biodiversity are projected to come from future global change," said Walter Jetz, an assistant professor of biological sciences at UC San Diego, who headed the study. "The developed nations are where the world's wealth is concentrated, but they are not the future battlegrounds for conservation."

Sifaka Lemur in Madagascar

Walter Jetz, UCSD

"While many details still have to be worked out, our study is a first baseline attempt on a global scale to quantitatively demonstrate the urgent need to plan reserves and other conservation efforts in view of future global change impacts," he added. "Reserves have often been set up haphazardly, following some national goal, such as to preserve 10 percent of a country's area, or in response to past threats. But little consideration has been given to the actual geography of future threats in relation to biodiversity. Yet it's those future threats that expose biodiversity to extinction."

Baobab Tree in Madagascar

Walter Jetz, UCSD

To conduct their study, the researchers examined the impact of climate and land use changes on networks of biological reserves around the world and contrasted them to four projections of future global warming, agricultural expansion and human population growth from the global Millennium Ecosystem Assessment. They discovered that past human impacts on the land poorly predicted the future impacts of climate change, revealing the inadequacy of current global conservation plans.

"The past can only guide you so much in the future," said Tien Ming Lee, a graduate student and the first author of the study. "This is why we may have to change our future conservation priorities if we want to be effective in conserving biodiversity in the long run."

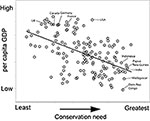

Lee said the study also confirmed the longstanding argument that wealthy countries with few threats to future biodiversity loss would do better to spent their conservation dollars on underdeveloped countries with greater threats of future extinctions than in their own backyards.

"Tropical countries are currently sitting on vast tracts of forests that are substantial carbon sinks and if they can get adequate financial help to protect these habitats, both global climate change and biodiversity loss could be mitigated," he said.

Funding for the study was provided by the National Science Foundation.

Fig 2: Regions with the greatest projected conservation need are those with the least current-day conservation resources. In this figure, high conservation need nations are those with little protected area in relation to projected land-use change and with a lot of threatened biodiversity. Note that wealth (per capita GDP) increases in 10-fold increments vertically, while conservation need increases linearly. Countries on the bottom right have the greatest projected conservation need but they are also the least wealthy, potentially hampering urgently needed conservation efforts. Many countries on the top left are wealthy, but from a global perspective that focuses on minimizing total species loss have relatively minor projected conservation need in their own backyard. The study offers an attempt to quantify and set into context future conservation needs at the global scale. But the results offer only broad trends, and the potential effects of e.g. geographical shifts in distributions and the special fate of high-altitude species were not considered in the analysis.