Study Finds Therapies Using Induced Pluripotent Stem Cells Could Encounter Immune Rejection Problems

May 13, 2011

By Kim McDonald and Chris Palmer

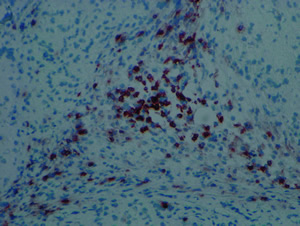

An infiltration of T cells, shown by dark brown color, can be seen in the tissues formed by iPSCs.

Credit: Yang Xu, UC San Diego

Biologists at UC San Diego have discovered that an important class of stem cells known as "induced pluripotent stem cells," or iPSCs, derived from an individual's own cells, could face immune rejection problems if they are used in future stem cell therapies.

In today's advance online issue of the journal Nature, the researchers report the first clear evidence of immune system rejection of cells derived from autologous iPSCs that can be differentiated into a wide variety of cell types.

Because iPSCs are not derived from embryonic tissue and are not subject to the federal restrictions that limit the use of embryonic stem cells, researchers regard them as a promising means to develop stem cell therapies. And because iPSCs are derived from an individual's own cells, many scientists had assumed that these stem cells would not be recognized by the immune system. As a consequence, the immune system would not try to mount an attack to purge them from the body.

In fact, scientists regarded iPSCs as particularly attractive candidates for clinical use because cells derived from embryonic stem cells will induce immune system rejection that requires physicians to administer immune suppressant medications that can compromise a person's overall health.

But the UCSD biologists, funded by NIH and an early translational grant from the California Institute for Regenerative Medicine, the state's stem-cell funding agency, found that iPSCs are subject to some of the same problems of immune system rejection as embryonic stem cells.

"The assumption that cells derived from iPSCs are totally immune tolerant has to be reevaluated before considering human trials," says Yang Xu, a professor of biology at UCSD who headed the team that published the study.

His team of biologists—which included postdoctoral researchers Tongbiao Zhao, Zhen-Ning Zhang and Zhili Rong—reached that conclusion after testing the immune response of an inbred strain of mice to embryonic stem cells and several types of iPSCs derived from the same strain of inbred mice.

The scientists found, not surprisingly, that the immune system of one mouse could not recognize the cells derived from embryonic stem cells of the same strain of mice. But the experiments also showed that the immune system rejected cells derived from iPSCs reprogrammed from fibroblasts of the same strain of mice, mimicking the situation whereby a patient would be treated with cells derived from iPSCs reprogrammed from the patient's own cells. The scientists also found that the abnormal gene expression during the differentiation of iPSCs causes the immune responses.

"This result doesn't suggest that iPSCs cannot be used clinically," says Xu. "It is important now to look at exactly what types of cells derived from iPSCs—and there probably are not that many based on our findings—are likely to generate immune system rejection."

"Our immune response assay is a robust method for checking the immune tolerance, and therefore, the safety of iPSC that may be developed," he added.

With grants from the California Institute for Regenerative Medicine, Xu's team is also developing strategies to minimize the formation of tumors that result from the use of human embryonic stem cells and to increase the immune tolerance of human embryonic stem cells.

Media Contact: Kim McDonald (858) 534-7572 or kmcdonald@ucsd.edu