Researchers Identify Gene That Helps Prevent Brain Disease

Protein 'proofreading' errors lead to neurodegenerative disease

May 17, 2018

By Mario C. Aguilera

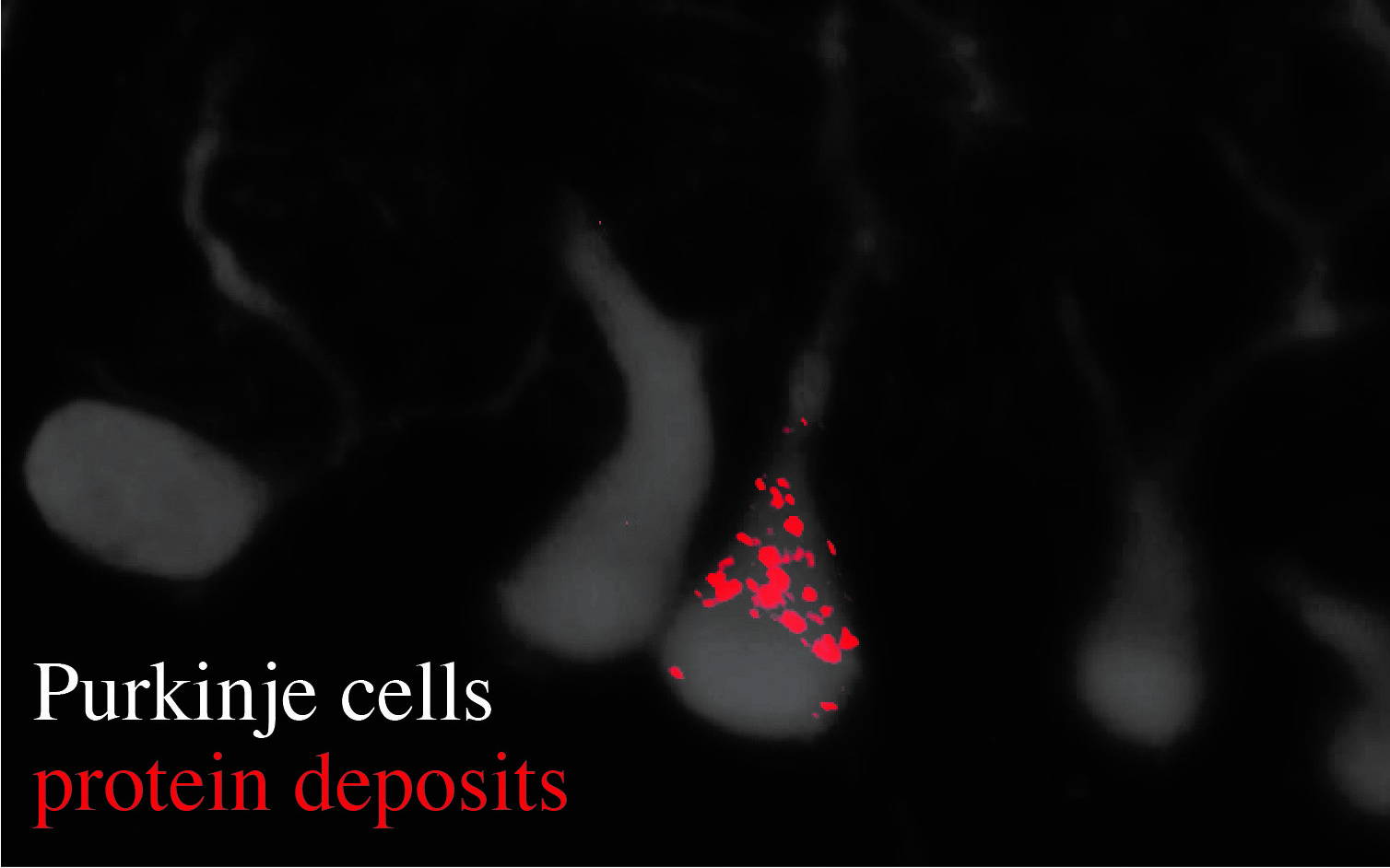

Image reveals Purkinje cells (gray) and their dendrites, as well as an accumulation of protein deposits (red dots)

Ackerman Lab/UC San Diego

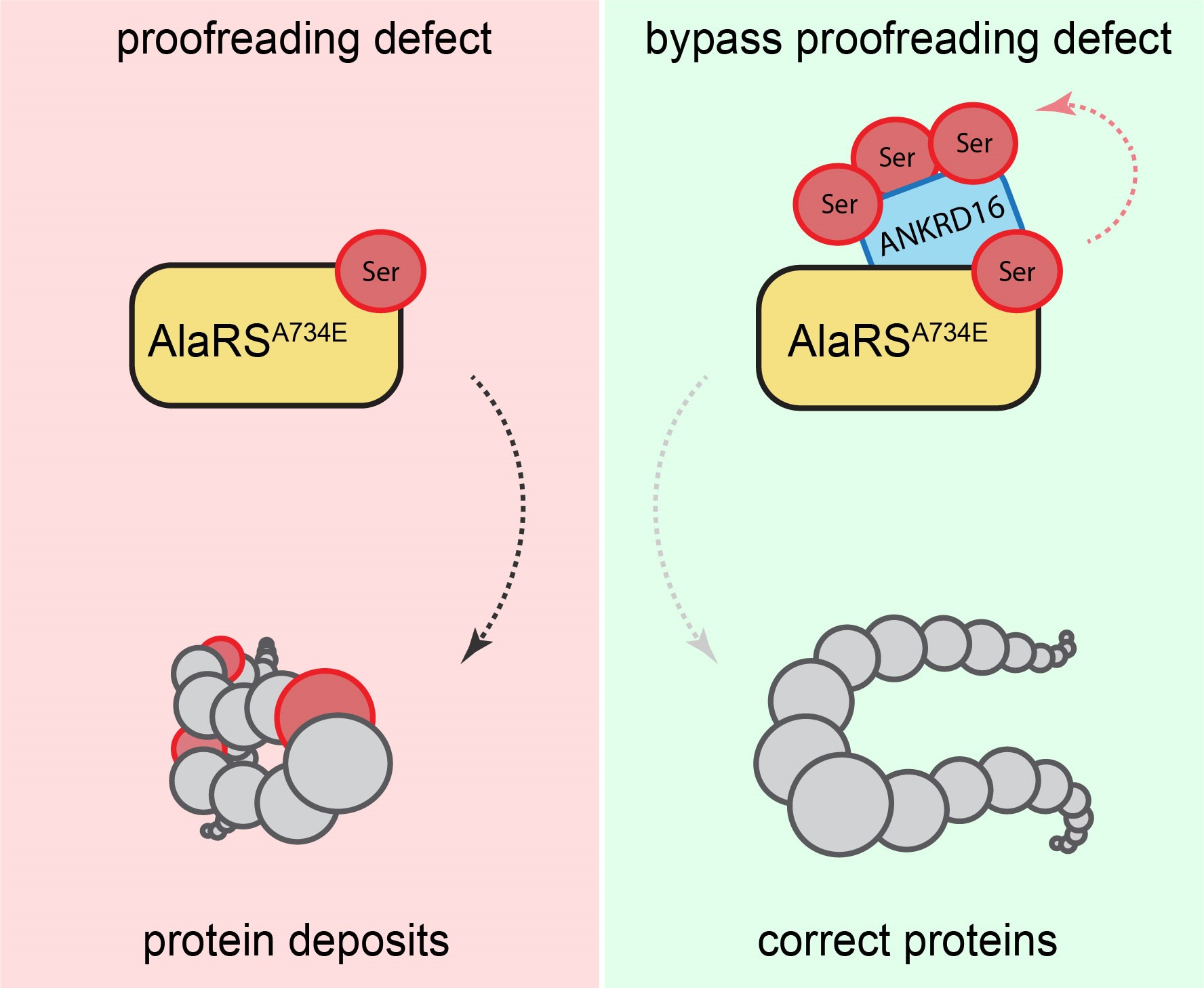

Scientists know that faulty proteins can cause harmful deposits or "aggregates" in neurological disorders such as Alzheimer's and Parkinson's disease. Although the causes of these protein deposits remain a mystery, it is known that abnormal aggregates can result when cells fail to transmit proper genetic information to proteins. University of California San Diego Professor Susan Ackerman and her colleagues first highlighted this cause of brain disease more than 10 years ago. Now, probing deeper into this research, she and colleagues have identified a gene, Ankrd16, that prevents the protein aggregates they originally observed.

Usually, the information transfer from gene to protein is carefully controlled—biologically "proofread" and corrected—to avoid the production of improper proteins. As part of their recent investigations, published May 16 in the journal Nature, Ackerman, Paul Schimmel (Scripps Research Institute) My-Nuong Vo (Scripps Research Institute) and Markus Terrey (UC San Diego) identified that Ankrd16 rescued specific neurons—called Purkinje cells —that die when proofreading fails. Without normal levels of Ankrd16, these nerve cells, located in the cerebellum, incorrectly activate the amino acid serine, which is then improperly incorporated into proteins and causes protein aggregation.

"Simplified, you may think of Ankrd16 as acting like a sponge or a 'failsafe' that captures incorrectly activated serine and prevents this amino acid from being improperly incorporated into proteins, which is particularly helpful when the ability of nerve cells to proofread and correct mistakes declines," said Ackerman, the Stephen W. Kuffler Chair in Biology, who also holds positions in the UC San Diego School of Medicine and the Howard Hughes Medical Institute.

The levels of Ankrd16 are normally low in Purkinje cells, making these neurons vulnerable to proofreading defects. Elevating the level of Ankrd16 protects these cells from dying, while removing Ankrd16 from other neurons in mice with a proofreading deficiency caused widespread buildup of abnormal proteins and ultimately neuronal death.

The researchers describe Ankrd16 as "…a new layer of the machinery essential for preventing severe pathologies that arise from defects in proofreading."

The researchers note that only a few modifier genes of disease mutations such as Ankrd16 have been identified and a modifier-based mechanism for understanding the underlying pathology of neurodegenerative diseases may be a promising route to understand disease development.

Coauthors of the paper include: Jeong Woong Lee and Hongjun Fu, formerly of The Jackson Laboratory in Bar Harbor, Maine; Bappaditya Roy, Qi Liu and Kurt Fredrick of the Ohio State University; James Moresco (now at the Salk Institute for Biological Studies), Litao Sun and John Yates III of the Scripps Research Institute; and Thomas Weber of Dynamic Biosensors.

The research was supported by the Howard Hughes Medical Institute, the National Institutes of Health (R01NS42613, R01GM072528 and R01CA92577), and a Fellowship from the National Foundation for Cancer Research.