UCSD Biologists Solve Plant Growth Hormone Enigma

JUNE 30, 2006

By Sherry Seethaler

Gardeners and farmers have used the plant hormone auxin for decades, but how plants produce and distribute auxin has been a long-standing mystery. Now researchers at the University of California, San Diego have found the solution, which has valuable applications in agriculture.

The study, published in the July 1 issue of the journal Genes and Development, describes the discovery of a whole family of auxin genes, and shows that each gene is switched on at a distinct location in the plant. Contrary to the current thinking in the field, the research shows that the patterns in which auxin is produced in the plant influence development, a finding that can be applied to improving crops.

"The auxin field dates back to Charles Darwin, who first reported that plants produced a substance that made them bend toward light," said Yunde Zhao, an assistant professor of biology at UCSD. "But until now, the auxin genes have been elusive. Our discovery of these genes and the locations where auxin is produced in the plant can be applied to agricultural problems, such as how to make seedless fruit or plants with stronger stems."

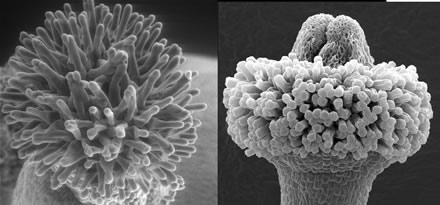

Electron microscope image of the female portion of a normal (left) and auxin-deficient (right) flower.

The researchers identified a family of 11 genes (YUCCA 1-11) that are involved in the synthesis of auxin. In Arabidopsis - a small plant favored by biologists because it is easy to manipulate genetically - Zhao's team inactivated combinations of the YUCCA genes and studied the effects of the inactivations on plant growth and development.

"Plant biologists have wanted to do this experiment for a long time, but only recently have new genetic tools such as 'reverse genetics' and 'activation tagging' made it possible," explained Youfa Cheng, a postdoctoral fellow working with Zhao. "Even with the advances in technology, it took about three years to produce plants lacking at least four of the 11 YUCCA genes."

Disrupting one YUCCA gene did not have any obvious effects. Therefore, there is overlap in the functions of the genes in this family. However, when two or more YUCCA genes were inactivated, the plants had developmental defects. The defects, including flowers with missing or misshapen parts, or deformations in the tissues that transport water and nutrients throughout the plant, differed depending on which combinations of genes were deleted.

The researchers say that this finding was surprising because most people in the field thought that where auxin was made did not really matter. The widely held view was that auxin could just be transported wherever it was needed. Not so, because turning auxin off in specific tissues of the plant led to defects in those tissues, while the rest of the plant appeared normal.

"Knowing which auxin genes are activated when should make it possible to modify plant development," said Zhao. "It wouldn't require adding any new genes to the plant, just changing when the appropriate auxin genes were on or off could alter growth. For example, to make seedless tomatoes, one could activate auxin in the floral organs before fertilization has taken place."

Applying auxin to the flowers by hand can also induce seedless tomatoes, or other seedless fruit, but this method is too tedious to be useful for commercial purposes. Seedless fruits would not just be novelty items. For example, Zhao points out that seeds significantly increase the effort and waste involved in producing tomato sauce.

"This study is a real tour de force," commented Martin Yanofsky, a professor of biology at UCSD, who was not one of the authors of the study. "People have been trying to figure out auxin for decades. By carefully inactivating the genes for auxin synthesis one by `one, the team was able to show how the localized production of auxin controls the architecture of a plant."

Xinhua Dai, a research associate working with Zhao, also contributed to the study. This research was supported by the National Institutes of Health.

Media Contact: Sherry Seethaler, (858) 534-4656

Comment: Yunde Zhao, (858), 822-2670